Here we illustrate why and how to implement RCC in NexRes, compare the RCC implementations in ResDB and NexRes and show the experiment results we got for RCC in NexRes.

The bottleneck in primary-backup BFT protocols

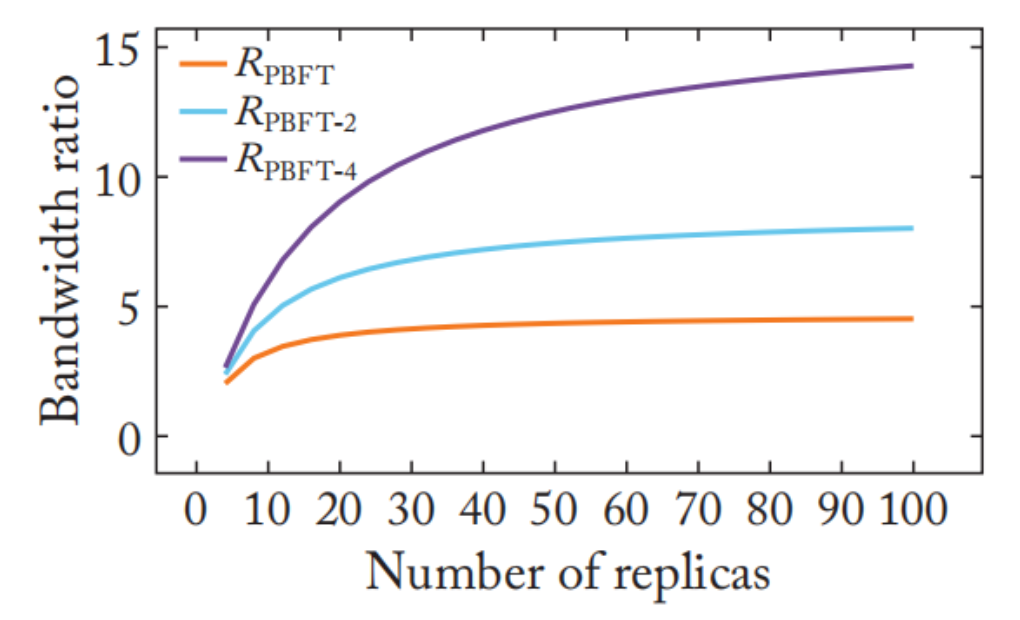

In traditional primary-backup protocols like PBFT1, a single primary broadcasts client requests to all other replicas. Thus, as the following figure shows, there is an unbalanced overhead of sending messages between primary and backup replicas. As the number of replicas increases, the imbalance is exacerbated. And the system performance bottleneck can be the primary’s outgoing bandwidth when the system is of large scale.

Figure 1. Unbalanced Overhead Between Primary and Backup Replicas

Resilient Concurrent Consensus (RCC)

The Resilient Concurrent Consensus paradigm RCC has been proposed to turn any primary-backup consensus protocol into concurrent consensus by running multiple instances concurrently. RCC is designed with performance in mind and ensures increased resilience against failures2.

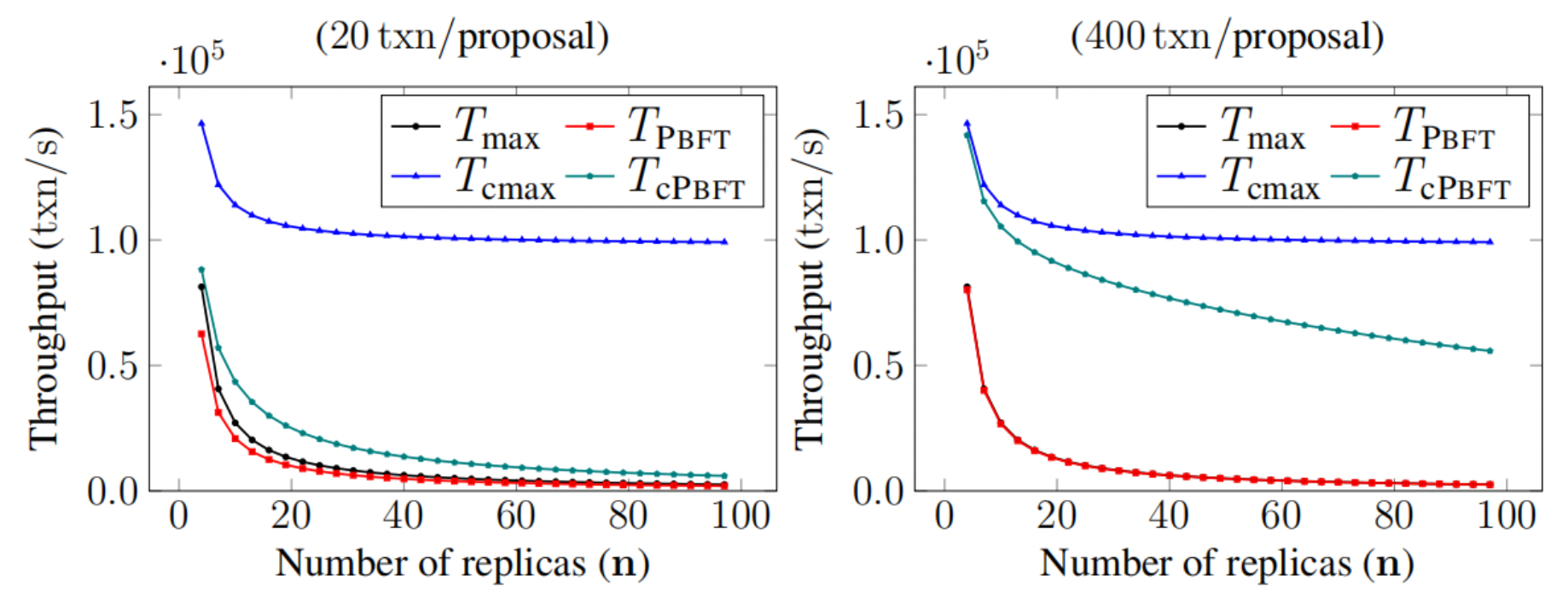

RCC runs multiple primary-backup consensus instances concurrently, distributing the overhead of broadcasting client requests to other replicas and overcoming the performance bottleneck caused by the primary’s outgoing performance. As the following figure shows, in theory, running concurrent instances has an impressionable positive impact on system throughput.

Figure 2. The Promise of Concurrent Consensus

ResDB vs NexRes

As a global-scale sustainable blockchain fabric, ResilientDB offers a high-throughput yielding distributed ledger built upon scale-centric design principles to democratize and decentralize computation. And RCC has been implemented in ResDB, the older version of ResilientDB. In ResDB, only one thread is assigned to one instance and CPU resources cannot be fully utilized for PBFT or RCC with a small number of instances. So, even though in the Resdb, RCC shows better performance than PBFT, which is consistent with our theoretical expectation, the actual bottleneck of PBFT is CPU utilization rather than bandwidth.

NexRes, the next generation of ResilientDB, assigns multiple threads to one instance, fully utilizing CPU resources to process messages. Then, CPU utilization is not the bottleneck for PBFT in NexRes. Running PBFT in NexRes is capable of saturating the primary’s network bandwidth, which meets the prerequisite for leveraging RCC to improve system throughput.

Implementation

In this section, we will give a brief overview of the implementation of RCC in NexRes. To implement RCC with concurrent instances in Nexres, adjustments in five modules are required: Configuration, Client, Primary, Backup Replica, and Total Ordering.

Configuration

To implement RCC in NexRes, first, we need to make changes in the configuration file, which specifies the number of instances and the primaries in the configuration file.

In the current implementation, we have the first m replicas to be primaries in m-instance RCC.

{

"region": [

{

"replicaInfo": [

## omitted

],

"regionId": 1

}

],

"selfRegionId": 1,

"instance": 4 # number of instances

}

Client

Clients send requests to all primaries evenly rather than a single primary as it does in PBFT.

uint32_t primary = total_num_ % config_.GetConfigData().instance() + 1;

replica_client_->SendMessage(*new_request, primary);

Primary

Running concurrent instances, replicas in RCC should be able to identify the instance of each message. Thus, for proposal messages, we need to use a field called instance to identify the instance of a proposal. With such a field, replicas can map messages to correct corresponding instances.

When broadcasting proposals, a primary needs to indicate its instance in the proposals.

client_request->set_instance(config_.GetSelfInfo().id());

replica_client_->BroadCast(*client_request);

Backup Replica

When receiving a proposal of instance i, a backup replica needs to check if it is exactly from the primary of instance i.

uint32_t instance_num = config_.GetConfigData().instance();

if ((uint32_t)(request->sender_id()) != request->instance() ||

(uint32_t)(request->sender_id()) % instance_num != request->seq() % instance_num)

{

LOG(ERROR) << "the request is not from a correct primary. sender:"

<< request->sender_id() << " seq:" << request->seq();

return -2;

}

Total Ordering

Before executing committed client requests, RCC orders the committed requests between different instances in the same round. So we need a mechanism to determine the execution order of committed transactions in one round. Now we adopt the simplest one, ordering transactions in the same round based on instance id, from the lowest instance to the highest one.

Experiment and Results

Experiment Setup

The experiments are done in AWS. The configuration of the machines we used is shown as follows:

- t3.2xlarge

- 8-vCPUs

- 32-GiB Memory

- Maximum Bandwidth: 600MB/s

The experiments used up to 96 replicas and 4 clients.

Experiment 1 - Scalability

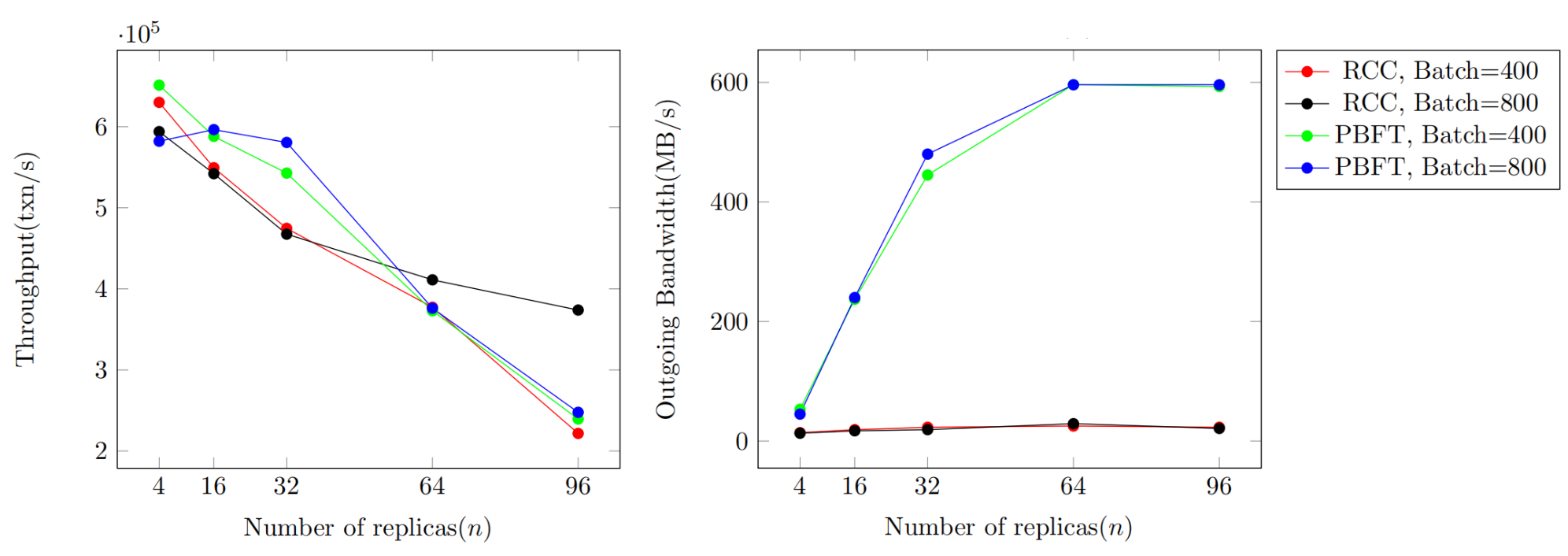

The first experiment is designed to compare the best-case throughput and outgoing bandwidth of RCC and PBFT of different replicas. The throughput and outgoing bandwidth of RCC and PBFT with different numbers of replicas are recorded. The replica number is set to 4, 16, 32, 64, and 96. The batch size is set to 400 and 800.

We denote RCC with batchsize B by RCC-B, and so does PBFT. As the system scales, throughput decreases. RCC-800 outperforms RCC-400, PBFT-800 and PBFT-400, when there are 96 replicas. From the right figure, we can see that PBFT-400 and PBFT-800 are bottlenecked by outgoing bandwidth. And the reason why RCC-400 has a lower performance than RCC-800 is that RCC-400 processes double number of consensus messages. Though RCC-400 gets rid of the bandwidth bottleneck, we’ve found RCC-400 happens to be bottlenecked by computing capability when there are 96 replicas by monitoring its CPU utilization, which is close to the maximal value i.e., 800%.

Figure 3. RCC Scalability Compared to PBFT

Experiment 2 - Batching

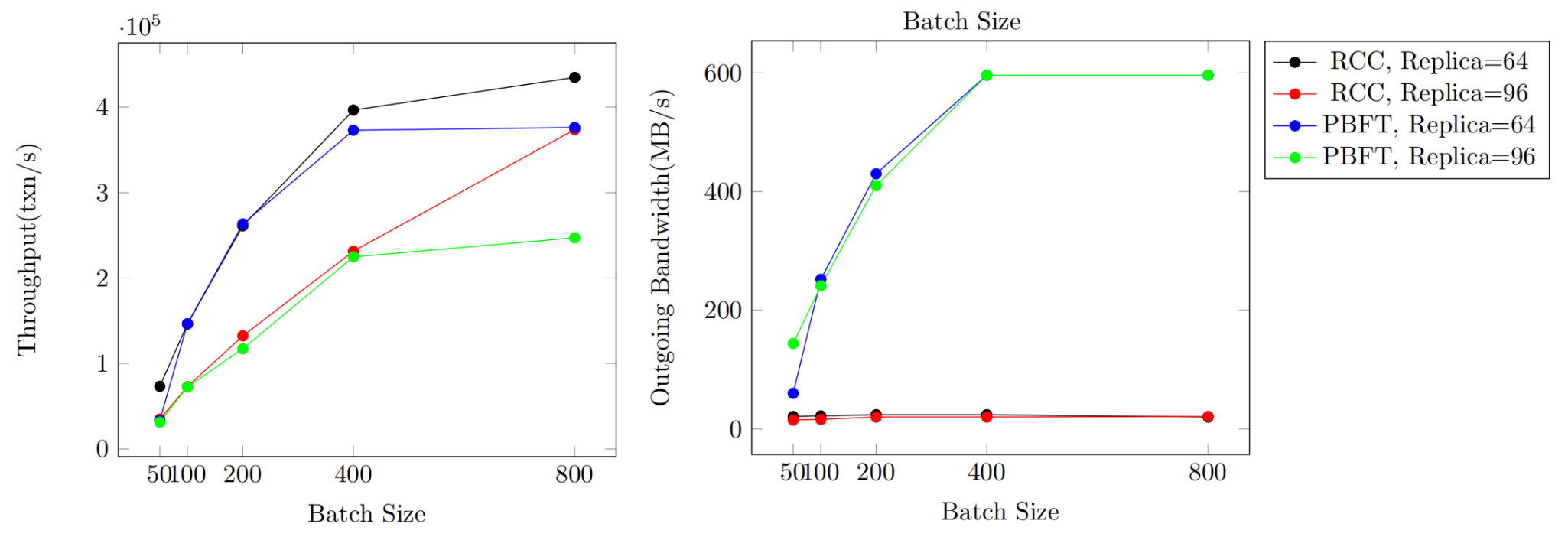

This experiment aims to test and record the throughput and outgoing bandwidth usage of PBFT and RCC with 64 or 96 replicas with different batch sizes. The batch size is set to 50, 100, 200, 400, and 800.

Experiment results show that increasing batch size benefits PBFT and RCC throughput when batch size increases from 50 to 400. Nonetheless, it makes no difference for PBFT when increasing batch size from 400 to 800, since PBFT is bottlenecked by outgoing bandwidth shown in Figure 6, while the throughput of RCC still increases.

Figure 4. Batching in RCC and PBFT

Experiment 3 - Larger Transaction Size

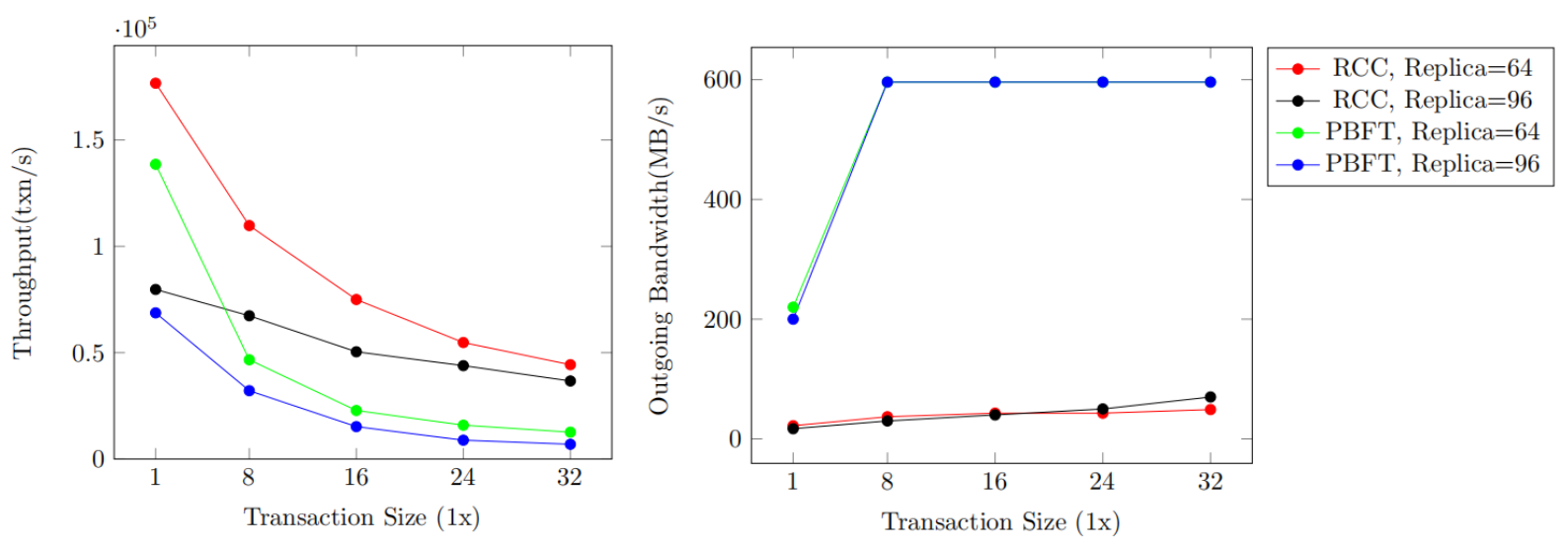

In this experiment, we test and record the throughput and outgoing bandwidth of RCC and PBFT, adopting transactions with different sizes but the same execution time. We test systems with 64 and 96 replicas, 1x, 8x, 16x, 24x, and 32x transaction sizes. We set the batchsize to 100.

As we can see from the figure, as the transaction size increases, limited by outgoing bandwidth, PBFT throughput decreases greatly. RCC also shows a throughput performance, but the throughput ratio between RCC and PBFT grows. We can safely draw the conclusion that RCC has a throughput advantage when processing transactions with large sizes.

Figure 5. Performance of RCC and PBFT with Larger Transaction Size

Experiment 4 - Concurrent Consensus

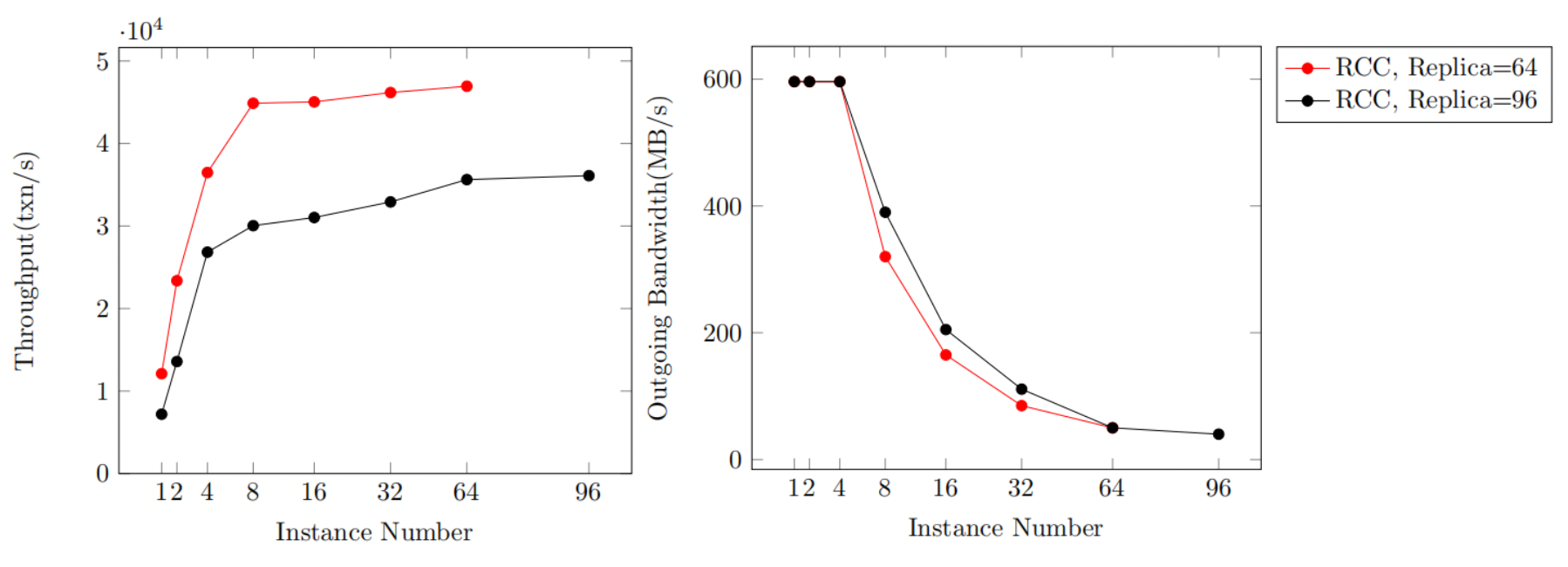

This experiment tests and records the throughput and outgoing bandwidth of RCC with 64 or 96 replicas with different numbers of instances. The batch size is set to 100 and we adopt a 32x transaction size.

In RCC, when there are 1, 2, or 4 instances, system performance is bottlenecked by the primaries’ outgoing bandwidth. As the number of instances increases, throughput increases linearly. The more instances RCC has, the more primaries share the overhead of broadcasting client transactions. With at least 8 instances, the primaries’ outgoing bandwidth is not saturated and the system throughput increases slightly with the instance number.

Figure 6. Effect of Concurrent Consensus on RCC

References

-

Castro, Miguel, and Barbara Liskov. “Practical byzantine fault tolerance.” OsDI. Vol. 99. No. 1999. 1999. ↩

-

Gupta, Suyash, Jelle Hellings, and Mohammad Sadoghi. “Rcc: Resilient concurrent consensus for high-throughput secure transaction processing.” 2021 IEEE 37th International Conference on Data Engineering (ICDE). IEEE, 2021. ↩